Designing Master Data Hierarchies That Actually Work

Last week, we talked about slowly changing dimensions, and why time matters more than most teams admit. Master data keeps moving because the business keeps moving. Companies merge, customers reorganize, and “the right value” today is not always the right value for last quarter’s report. If you overwrite everything, you lose the story behind the numbers. If you try to preserve every tiny change, you end up with a history nobody can use. SCD is really about making smart choices around what to track, how to track it, and how to keep reporting honest.

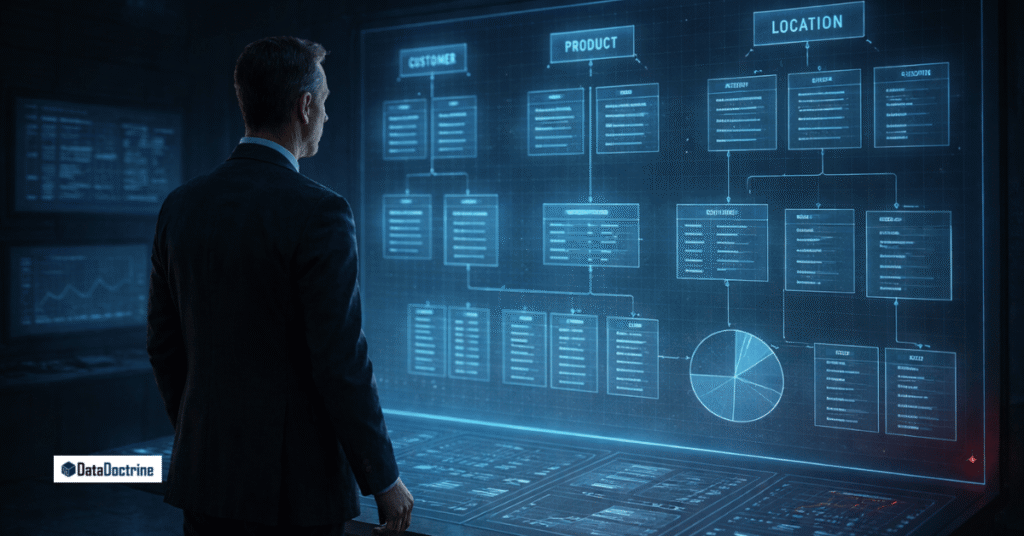

This week stays in that same lane, but shifts from time to structure. A hierarchy is your answer to a simple question: what rolls up into what? It’s how you decide whether two records belong to the same parent, whether a product sits in one category or another, and which level the business should use when it wants totals that make sense. When the hierarchy is unclear, the cracks show up fast. You see duplicate records, rollups that do not match across systems, and meetings where people argue over who has the “right” view. When the hierarchy is designed with purpose, it becomes one of those quiet foundations you stop thinking about because it just works.

Many master data hierarchies fail, but not because of tools. Instead, it they fail due to either flawed business assumptions or rigid design. Far too often, teams try to model real-world relationships in a way that’s either too brittle, too shallow, or too abstract. We will explore how to design master data hierarchies that support both operational systems, as well as analytics, with long-term maintainability in mind.

Why Master Data Hierarchies Matter

Hierarchies shape how data is grouped, aggregated, and understood. When they’re done right, they power financial roll-ups, sales analytics, territory management, security permissions, etc. When they’re done poorly, the fallout spreads far and wide, typically showing up as duplicated records, misaligned reports, and fractured workflows.

A master data hierarchy isn’t just an org chart. It’s a structural backbone for domains like customer, product, location, and chart of accounts. Every domain depends on hierarchies to define relationships and make sense of entity-level data across systems.

Well-structured hierarchies ensure every team is speaking the same language about key entities. If one department rolls up a customer to “Parent Company A” and another to “Global Entity X,” it undermines reporting, planning, and customer insight. Hierarchies tie together disparate records and make business relationships explicit.

Types of Master Data Hierarchies

Customer Hierarchies

In B2B, customer hierarchies reflect corporate structures. One global account might own dozens of regional entities. Without a hierarchy, each entity may appear isolated. That leads to fractured sales coverage, missed cross-sell opportunities, and inconsistent credit terms.

Customer hierarchies typically include:

- Global Ultimate Parent

- Regional Parents

- Subsidiaries and Branches

- Billing Entities

- Ship-To Locations

They allow you to:

- Roll up contract exposure

- Consolidate invoicing

- Manage credit at the parent level

- Align sales and account coverage

In B2C, household hierarchies are sometimes used to group individuals into family units. This helps with personalized offers and privacy controls.

Product Hierarchies

Product hierarchies group SKUs into categories that mirror how companies manage their product lines. They support:

- Inventory planning

- Procurement strategies

- Site navigation and merchandising

- Financial reporting by product line

A common structure:

- Division (e.g., Electronics)

- Department (e.g., Computing)

- Category (e.g., Laptops)

- Subcategory (e.g., Gaming Laptops)

- SKU

Internal teams may use deeper structures with technical attributes, while public-facing views are kept simpler for usability.

Location Hierarchies

These support roll-ups by geography and operational structure. Examples include:

- Country > Region > District > Store

- Head Office > Division > Department > Team

They help with:

- Sales territory alignment

- Supply chain planning

- Facility maintenance

- Operational reporting

Standardizing on geographic codes (e.g., ISO country codes) helps align with third-party data and partners.

Chart of Accounts

The financial hierarchy governs how accounts are grouped for budgeting, forecasting, and reporting. It influences:

- P&L and balance sheet structure

- Internal cost tracking

- Legal and regulatory compliance

Typical layers:

- Business Unit

- Cost Center

- Account Type

- Account Code

Mistakes here lead to serious audit and compliance issues. Strong controls and versioning are essential.

Best Practices for Hierarchy Design

Define Each Level Clearly

Start with definitions. Don’t assume users agree on what “region” or “category” means. Document each level’s purpose. Use examples. Avoid vague labels like “miscellaneous” or “other.”

Each hierarchy should have:

- A clear business purpose

- Defined levels with unique meanings

- Examples of what belongs where

Consistency matters. If “Region” means geography in Sales and business unit in Finance, someone’s going to get burned. Create cross-functional definitions where possible.

Use Parent-Child Relationships

Adjacency modeling (where each record stores its parent ID) is flexible and easy to manage. It supports infinite depth and is well-supported in SQL and most MDM tools.

Advantages:

- Easy to update a single node’s parent

- Efficient to traverse for most operational uses

- Works with most BI and reporting tools

Some teams prefer nested set models or path enumeration, especially in analytics. Choose based on access patterns.

Enforce Referential Integrity

Nothing breaks trust like orphaned records. Every node must link up to a valid parent unless it’s a defined root. Systems should:

- Reject inserts with invalid parents

- Flag orphans in validation reports

- Use placeholder parents sparingly and temporarily

Your ETL and MDM processes must treat hierarchy linkage as a first-class validation. Don’t allow bad structure to persist in your golden record.

Balance Simplicity with Detail

Too few levels and you lose meaningful roll-ups. Too many and the hierarchy becomes unmanageable. Strike a balance:

- Limit depth to what teams actually use

- Avoid single-child branches unless meaningful

- Group sparsely populated nodes when possible

If a hierarchy has wild imbalance (e.g., one branch goes five levels deep while the rest stop at two), investigate. It could be modeling drift.

Allow for Alternate Hierarchies

A customer may need to be grouped by:

- Legal ownership (for finance)

- Industry vertical (for marketing)

- Sales territory (for sales ops)

Trying to force all needs into one hierarchy leads to conflict. Create parallel hierarchies or use attribute tagging to support multiple views.

Alternate hierarchies should be:

- Clearly scoped and named

- Owned by specific business units

- Sourced from the same golden master

MDM tools can support multiple hierarchy types per entity. Design for it from the start.

Align With Standards

Use standard codes and taxonomies where they exist. Benefits include:

- Easier integration

- Better third-party data matching

- Faster onboarding for new systems

Examples:

- UNSPSC or GS1 for product classification

- ISO region and country codes for locations

- D&B D-U-N-S numbers for corporate entities

Map internal codes to standards when possible. It saves time and reduces translation effort later.

Assign Clear Ownership

Each hierarchy (and each type of hierarchy) needs a steward. That person or team:

- Approves structure changes

- Reviews proposed reassignments

- Resolves conflicts

No ownership means chaos. Changes get made without oversight. Competing structures appear. Data consumers stop trusting the hierarchy.

Use RACI matrices for governance tasks. Involve both technical and business roles.

Supporting Operational and Analytical Use Cases

Operational Systems

These systems need lean, current hierarchy data. CRMs, ERPs, and support tools may only consume 1–2 levels of structure.

Tips:

- Push down only what’s needed

- Flatten if necessary (e.g., store both immediate and top-level parent)

- Keep updates near real-time

Some platforms struggle with recursive logic. Test how your hierarchy structure performs under expected load.

Analytical Systems

These platforms need rich, historical, and flexible structure. Data warehouses and BI tools must:

- Roll up data to multiple levels

- Support historical hierarchy snapshots

- Accommodate what-if simulations (e.g., what if Region A moved under Division X?)

Techniques:

- Precompute ancestor-descendant paths

- Store valid_from / valid_to dates for each relationship

- Track version IDs for each hierarchy snapshot

If you change a node’s parent, preserve history. Otherwise, past reports may change retroactively. This breaks trust and compliance.

Design your warehouse to accommodate multiple hierarchy perspectives. Tag facts with multiple hierarchy keys when needed.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

One-Size-Fits-All Structures

Don’t try to create a universal hierarchy. It will satisfy no one. Instead:

- Define separate hierarchies for each business need

- Govern each one independently

- Use consistent IDs to link across views

Conflicting Hierarchies in Different Systems

Without MDM, each platform creates its own truth. The same customer may belong to different regions in CRM and ERP.

Solve this by:

- Creating a single source of truth

- Publishing authoritative hierarchy data downstream

- Forcing consuming systems to subscribe, not author

Orphaned and Misclassified Nodes

Poor onboarding and lack of validation often lead to hierarchy breaks. These silently affect roll-ups and reports.

Fix this with:

- Required hierarchy fields in creation forms

- Data quality dashboards for orphan monitoring

- Escalation paths for fixing bad assignments

Over-Engineering

Just because you can build 10 levels doesn’t mean you should. Complex hierarchies:

- Are hard to train users on

- Require more governance effort

- Slow down reporting

Simplify wherever you can. Depth should serve a purpose.

Inflexible Design

Businesses change. Hierarchies must too. Design for:

- Re-parenting with history preserved

- New levels added without schema rework

- Easy visualization and simulation

Lack of flexibility forces shadow hierarchies. That erodes trust in the master structure.

No Audit Trail

When something changes, users will ask:

- When did this node move?

- Who approved it?

- What did the structure look like last quarter?

Without audit trails, you’ll rely on gut feel and guesswork. Always track change logs and snapshots.

Example Hierarchy and Real-World Results

Let’s walk through a realistic B2B customer hierarchy:

- Acme Global

- Acme Europe

- Acme Germany GmbH

- Acme France SARL

- Acme North America

- Acme USA Inc

- Acme Canada Ltd

- Acme Europe

Finance wants legal roll-ups by region. Sales wants segmentation by vertical market. Marketing wants top billing for largest spenders.

Without a managed hierarchy:

- Duplicate entries for Acme USA and Acme Canada show up in CRM

- Reports don’t show total spend

- Legal reviews are manual

With a managed hierarchy:

- Sales see a 360-degree view of the account

- Legal knows where exposure lies

- Finance can track credit by parent

In one real-world case, a global supplier consolidated five versions of the customer hierarchy from regional CRMs. The result:

- 15% fewer customer records after deduplication

- 22% improvement in quote-to-close time

- Accurate cross-sell and upsell targeting

Product hierarchies show similar gains. Retailers that align item classification across systems reduce onboarding time for vendors and increase speed to market.

Final Thoughts on Hierarchy Sustainability

A good hierarchy today isn’t enough. It needs to stay good over time. That means:

- Ongoing stewardship: Regular reviews and stakeholder engagement

- Change processes: Structure re-orgs need planning, sign-off, and validation

- Clear communication: Notify downstream users when hierarchy changes

- Training: New employees must understand how to navigate and use hierarchies

- Documentation: Capture rules, levels, examples, and decision history

Your hierarchy is a strategic asset. Design it with care. Govern it with discipline. And revisit it with curiosity. If done right, it quietly powers everything from daily reports to board-level insight.

Don’t wait for a reporting disaster to prioritize it. Start now.