Avoiding Frankenmodels in Master Data Management Design

In last week’s post, Stop Overloading the Customer Domain in Master Data Models, we tackled the dangers of stuffing every entity into the Customer table. It’s a design shortcut that muddies semantics, confuses governance, and makes your master data harder to trust.

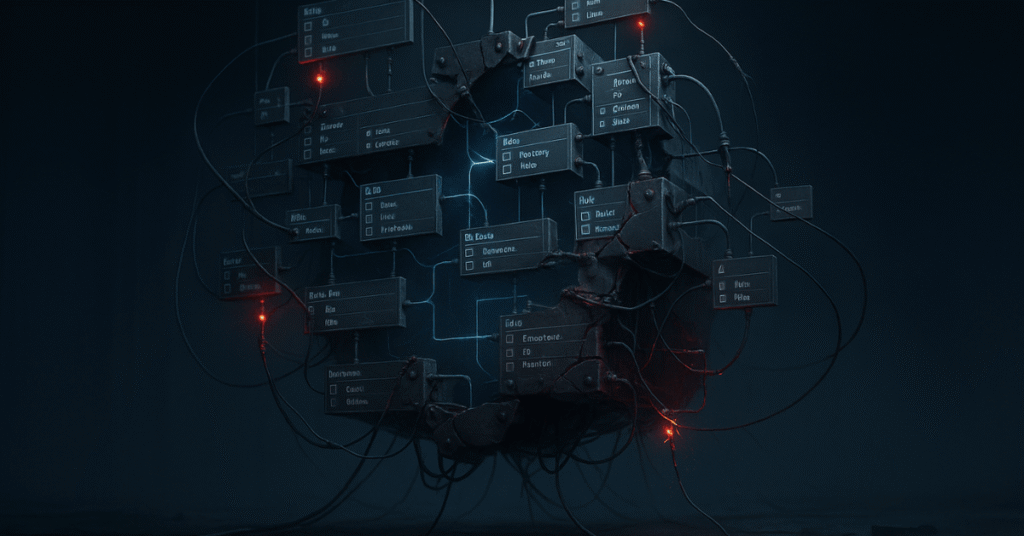

But overloaded domains aren’t the only design trap. This week, we’re shifting focus to a different kind of monster: the Frankenmodel. Born from quick fixes, one-off integrations, and unchecked exceptions, these models limp along until they collapse under their own weight. In this post, we’ll break down how Frankenmodels happen, why they’re so hard to maintain, and the patterns that help you avoid creating one in the first place.

When Good Models Go Bad

You’ve probably seen one.

Maybe you’ve even had the misfortune of inheriting one.

It starts as a clean, logical data model, a thing of beauty. But over time, little compromises creep in. A new field here. A one-off relationship there. A “quick” workaround that somehow becomes permanent. Before you know it, you’re looking at a structure that technically works, but feels like it was assembled from spare parts.

This is the Frankenmodel, a master data model stitched together without a clear plan, limping along under the weight of mismatched logic, conflicting definitions, and inconsistent governance. It looks like a data structure, but behaves like chaos.

The good news? You can prevent them. And if you already have one, you can start taming it.

What Is a Frankenmodel in MDM?

A Frankenmodel is a master data structure that has evolved through ad hoc changes rather than intentional, principle-driven design.

Common signs you’re dealing with one:

- Fields that only apply to a subset of records, creating wasted space and confusion

- Generic tables that try to represent many entity types at once, with rules that contradict each other

- Multiple role flags like

IsCustomer,IsVendor,IsPartnercrammed into the same record - Relationships that exist solely to solve a short-term problem, not to reflect actual business reality

- Edge-case logic baked into the schema itself instead of handled through process or rules

If your model requires a guided tour for every new developer, leaves business users second-guessing reports, or forces governance teams to apply rules inconsistently, it’s a Frankenmodel.

How Frankenmodels Are Born

Most Frankenmodels don’t start out broken. They start as thoughtful designs that degrade under pressure.

Here’s how it happens:

- Delivery deadlines override design discipline – “We’ll fix it later” becomes “We’ll live with it forever.”

- No centralized architecture review – Changes slip through without a holistic view of the impact.

- Integration-driven changes – The schema bends to fit a new source system without revisiting the bigger picture.

- The “one entity to rule them all” trap – Stakeholders insist everything live in one domain, often the “Customer” table.

- Workarounds become canon – Temporary fixes are never revisited, and exceptions quietly become the rule.

Each decision might seem harmless in isolation. Together, they tangle your model into something fragile, inconsistent, and hard to scale.

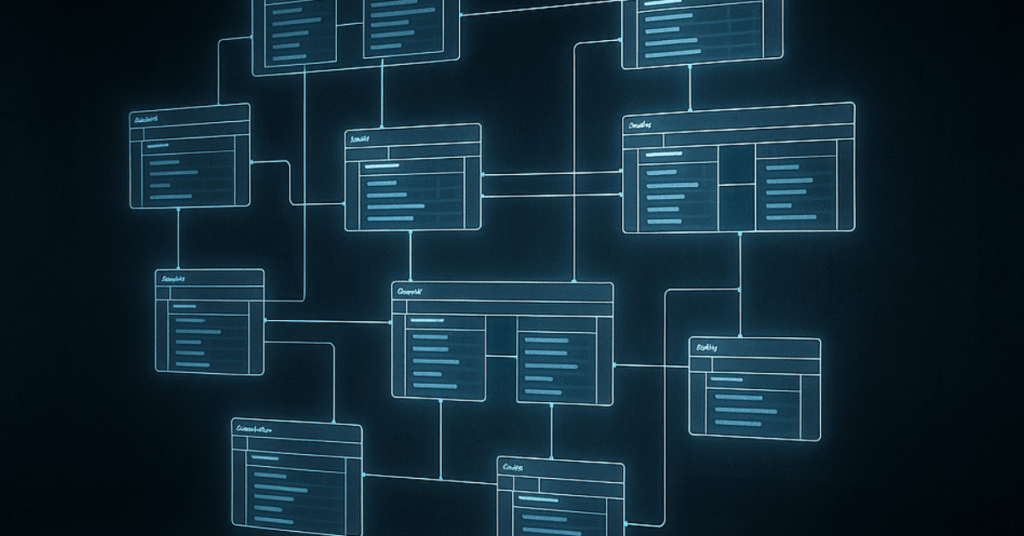

What a Scalable, Governed MDM Model Looks Like

A scalable master data model is deliberate. It separates concerns, uses clean abstraction, and is built to support governance, not fight it.

1. Separate Core Identity from Roles

Don’t overload your base entities with role-specific fields.

Instead, model the entity’s identity once, and define roles through relationships.

Example:

A person can be a customer, a vendor, and an employee. Their core attributes (name, birthdate, ID) don’t change. What changes is the role they play in different business processes.

2. Use Inheritance Where Appropriate

When different record types share common attributes, abstract those into a parent entity.

Create subtypes for the differences.

Example:

A “Product” might be a finished good, a service, or a raw material. Each shares some attributes (SKU, description) but also has unique ones. Modeling these as subtypes keeps validation rules tight and avoids a swamp of nullable columns.

3. Avoid Generic Catch-All Tables

Tables named “Entity” or “Party” seem flexible, but they often create semantic confusion and force you to write exception logic for nearly every case.

If you need multiple flags to describe what a record is, or if most rows use only a handful of the available columns, it’s a signal the model needs to be split.

4. Design with Governance in Mind

Every field should have an owner, a purpose, and a rulebook. Before adding a column, ask:

- Who owns it?

- What validation applies?

- Who can approve changes?

- How is it used downstream?

When governance is built into the model, you don’t just get better data quality, you get consistency that survives the next integration or system upgrade.

What to Do If You Inherit a Frankenmodel

Sometimes the monster’s already on your desk. You can’t rebuild it overnight, but you can start taming it:

- Document which fields are active, and mark the rest for deprecation

- Identify edge-case columns that only apply to a tiny fraction of records

- Separate roles from core identities, even if it means building new tables alongside the old

- Review relationships and remove or normalize the ones that don’t reflect real-world interactions

- Engage both technical and business stakeholders to validate proposed changes

Iterative cleanup beats paralysis. Every small step toward a cleaner, more consistent design makes the model more resilient and the data more trustworthy.

Final Thought: Your Data Model Is Your MDM Blueprint

Your master data model isn’t just a technical artifact, it’s the blueprint for how your organization defines and connects its most important entities.

If that blueprint is patched together from shortcuts and exceptions, no amount of tooling will rescue it.

Good MDM starts with good modeling. And good modeling comes from clarity, ownership, and the courage to say “no” when someone asks for “just one more field.”