Dead Letter Queues in SQL Server: How to Fail Gracefully Without Losing Data

What is a Dead Letter Queue? Imagine the following scenario:

Your pipelines are flowing. Your logic is sound. Your retry strategy is solid.

And yet… some records still fail.

Maybe it’s a missing foreign key. Maybe it’s a malformed payload. It could simply be just a rare edge case.

It doesn’t matter what causes the commit failure. Your pipeline needs a way to handle it without crashing.

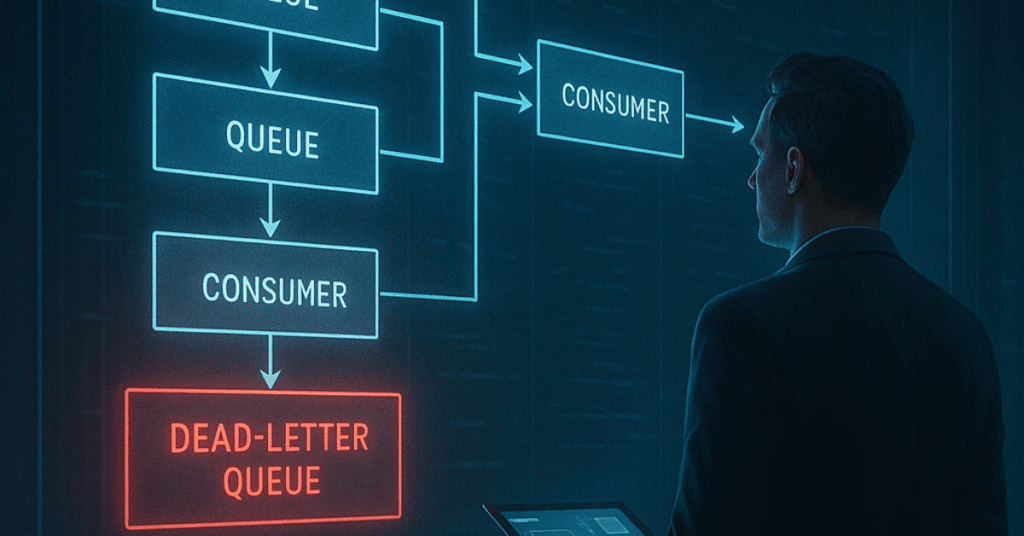

Enter the Dead Letter Queue (DLQ). The DLQ is your pipeline’s safety net. It serves as the last line of defense for when records fail to commit.

In this post, we’ll break down what a DLQ is, why it matters, and how to implement a simple, SQL Server–friendly version.

What’s a Dead Letter Queue?

A Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) is a place to send records that fail processing. Think of it as your data pipeline’s “lost and found.”

Instead of having records endlessly stuck inside of a retry loop (with no hope of ever committing), or worse, dropping the failed record completely, bad records get sent to the DLQ. This is where we can hold onto the original data, the error message, and the failure context – all of which helps us identify what went wrong so we can fix it.

Fail gracefully. Don’t bring everything down with one bad record.

DLQs are common in enterprise-level systems like Kafka, RabbitMQ, and Azure Service Bus; however, you don’t need one of these message brokers to use this pattern. It works just as well in SQL Server (or your database management system of choice), especially for smaller teams with limited resources.

Why Your ETL Needs a DLQ

If your current pipeline does this:

- Crashes when one record fails

- Logs a vague “error” somewhere deep in a job log

- Or worse, swallows the failure completely…

You’re setting yourself up for silent data loss or operational fires.

A DLQ solves that by:

- Isolating toxic data so it doesn’t block clean records

- Tracking and auditing what failed and why

- Enabling remediation, manually or automatically

The result? More resilient pipelines…and more sleep at night.

Designing a Dead Letter Table in SQL Server

Use this basic table structure which captures what you’ll need:

CREATE TABLE dbo.DeadLetterQueue (

DLQID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY,

SourceTable SYSNAME,

RecordID INT,

Payload NVARCHAR(MAX),

ErrorMessage NVARCHAR(4000),

ErrorCode INT,

AttemptCount INT DEFAULT 0,

InsertedAt DATETIME2 DEFAULT SYSDATETIME(),

Processed BIT DEFAULT 0

);

Consider adding more detail to better support your team: user ID, environment, stage name, etc.

Adding DLQ Logic to Your T-SQL ETL

Here’s a simplified pattern using TRY...CATCH:

BEGIN TRY

-- Attempt to insert clean data

INSERT INTO dbo.TargetTable (Col1, Col2)

SELECT Col1, Col2

FROM dbo.StagingTable;

END TRY

BEGIN CATCH

-- Capture failed record(s) and route to DLQ

INSERT INTO dbo.DeadLetterQueue (SourceTable, RecordID, Payload, ErrorMessage, ErrorCode)

SELECT

'StagingTable',

S.ID,

(SELECT * FROM dbo.StagingTable WHERE ID = S.ID FOR JSON AUTO),

ERROR_MESSAGE(),

ERROR_NUMBER()

FROM dbo.StagingTable S

WHERE <some logic to isolate bad rows>;

END CATCH;

📌 Pro tip: Structure your staging logic so you can easily isolate individual records that caused failures, especially if using batch inserts.

Monitoring the DLQ

Your DLQ isn’t just a place to stuff bad data. It’s a dashboard waiting to happen.

Start with this query to track volume:

SELECT

CAST(InsertedAt AS DATE) AS FailureDate,

COUNT(*) AS Failures

FROM dbo.DeadLetterQueue

GROUP BY CAST(InsertedAt AS DATE)

ORDER BY FailureDate DESC;

Set alerts if volume spikes. Track error codes. Make the invisible visible.

Retrying and Remediating

Dead letters aren’t dead forever.

Here are a few common patterns:

- Manual Retry: Build a stored procedure that reprocesses fixed records.

- Auto Retry: Use a SQL Agent job to retry any record with

Processed = 0andAttemptCount < 3. - Archive After Retry: Move resolved records to a historical DLQ table.

Example retry logic:

UPDATE R

SET Processed = 1

FROM dbo.DeadLetterQueue R

WHERE EXISTS (

SELECT 1

FROM dbo.StagingTable S

WHERE S.ID = R.RecordID

-- Add retry logic or validation conditions here

);

Bonus: Track AttemptCount to limit retries and avoid infinite loops.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even good DLQs can go bad. Watch out for these:

| Pitfall | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Never reviewing the DLQ | Silent failure buildup |

| Storing too little context | Debugging becomes guesswork |

| Retrying blindly | Can cause cascading errors |

| Not integrating with alerting | Ops team stays in the dark |

Make sure someone owns DLQ review and remediation. Don’t let it become the junk drawer of your data estate.

DLQs Beyond SQL Server

DLQs are everywhere in modern architecture:

- Kafka → Topic-level DLQs

- RabbitMQ → Message routing with rejection logic

- Azure Service Bus → Dead-letter sub-queues with automated isolation

In hybrid stacks, your DLQ(s) may live in multiple places. The principles of isolate, log, and retry remain constant, even if your DLQ implementations vary.

Final Thoughts

DLQs enable you to build data pipelines that are resilient and easy to audit, and who doesn’t want that?

And in SQL Server? It can be as easy as adding a single table. What is most important is how you design, monitor, and use it when things start to break.

Get practical MDM tips, tools, and updates straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for weekly updates from Data Doctrine.